In the article below Peter Crow discusses why despite the plethora of the recommendations on corporate governance and best practice, boards’ efficacy can remain in question.

The focus of the board is often reduced to compliance, monitoring historical performance and ensuring regulatory requirements are satisfied.

Directors must shift from merely ensuring rules are followed (and often working to protect personal and professional reputation above the companies they govern) to working together in pursuit of agreed performance goals and putting the best interests of the company first.

Key areas for effective board performance which directors would do well to note are:

- Prioritising long term and impartial thinking in decision-making associated with communications strategy

- Collective efficacy, where cooperation and working together to make informed decisions in strategic communications is prioritised

- Constructive control, where decisions around communications are made to align with the long-term strategy and goals of the organisation

Rob

Towards More Effective Corporate Governance

From hardly rating a mention in twenty or thirty years ago, boards have become quite newsworthy over the last decade or so.

Questionable practices and failures of various kinds have seen boards become topical; often targets of criticism in the eyes of the business media, regulators and, increasingly, the wider public. In addition, the previously little-used term that describes what boards do – corporate governance – has become ubiquitous, hackneyed even, to the point now of being invoked as a perpetrator or panacea for all manner of corporate activity, regardless of whether the board is involved or not.

Amidst this, many well-intentioned directors do not seem to understand their duties and responsibilities particularly well; privately admitting they have become confused about the purpose and role of the board, what corporate governance is and how it should be practiced.

This article discusses some of the issues that impair board effectiveness, before suggesting an alternative approach for more effective outcomes.

A challenging context

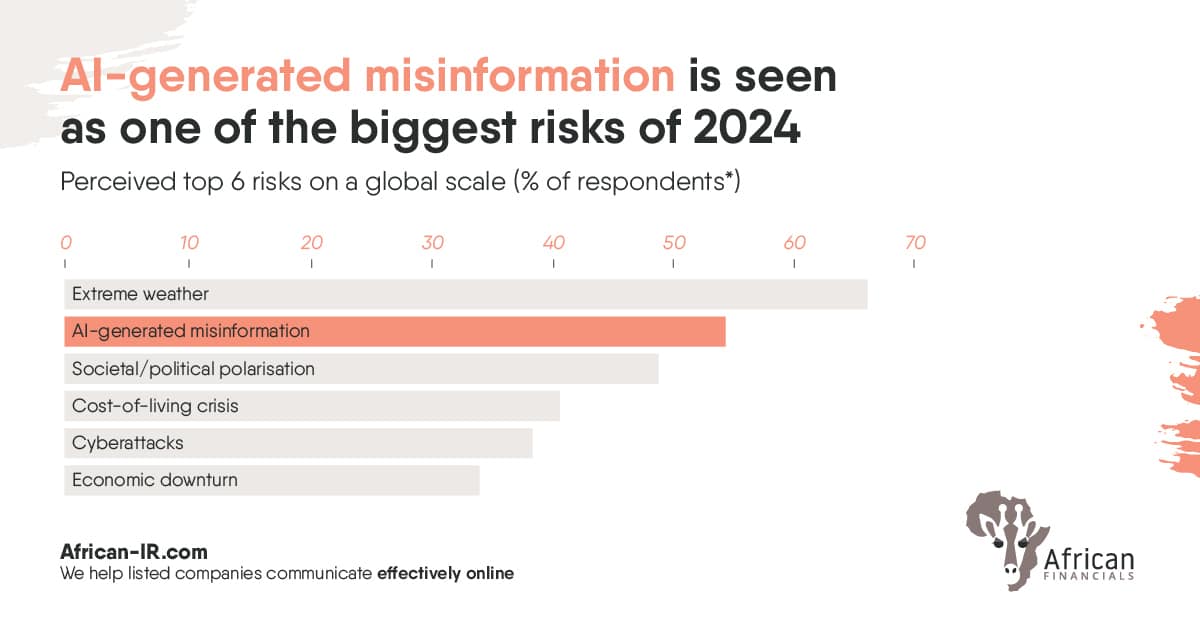

Modern boards face many challenges and complexities. Seismic geo-political shifts; the rise of populism and the diversity agenda; changing shareholder expectations, especially in relation to ESG; the onset of a global pandemic; and, risks of many types, especially terrorism and cyber-risk mean boards cannot take too much for granted in a dynamic marketplace.

Guidance to assist boards navigate this landscape and achieve ‘best practice’ is not in short supply. In fact, a surfeit of recommendations has now pervaded academies, directors’ institutes, and boardrooms.

Many countries have introduced codes and regulations as well, both to limit malfeasance and to provide boundaries and guidance to boards. Amongst them, a clear separation between the functions of governance and management; diversity of various forms; say-on-pay; and, independent directors have been promoted at various times, as precursors to effective board practice.

Many boards and shareholders have been enthralled by recommendations proposed to date, as they have searched for a definitive board configuration to suit their purposes.

But what of the efficacy of these recommendations?

Despite the best of intentions, the plethora of recommendations and codes now in circulation have yet to have the intended effect. Instead, the continuing and seemingly endless stream of corporate failures and significant missteps emanating from boardrooms suggests that contemporary ‘best practice’ recommendations provide little assurance of board effectiveness, much less company performance.

Studies of company and board failures reveal a consistent pattern of contributory factors. These include hubris and overconfidence amongst directors; low levels of board–management transparency; assertive CEOs that ‘take over’; lack of a critical attitude, genuine independence, appropriate expertise, and relevant knowledge in the boardroom; and, tellingly, low levels of commitment by directors.

Further, first-hand observations of boards in action show that the dominant focus is compliance; monitoring historical performance and checking regulatory requirements are satisfied.

The protection of professional and personal reputation is clearly a more powerful motivation for many directors than the performance of the company they govern. It is little wonder regulators are active and public confidence is low.

Focus on what matters

In sport, it’s well known that rules define boundaries not outcomes; teams that focus on the rules rarely win. The correspondence to boards and governance is direct.

“‘Best practice’ recommendations and codes are, essentially, rules. To focus strongly on them, without also considering the purpose and function of boards, is short-sighted”.

If boards are to become more effective in fulfilling their value-creation mandate, directors need to focus on what matters, especially discovering how best to work together in pursuit of agreed performance goals, with the best interests of the company to the fore.

This is made plain by Bob Tricker, a doyen of corporate governance. He argued, straightforwardly, that the purpose of the board is to govern, which includes overseeing the formulation of strategy and policy, supervision of executive performance, and ensuring corporate accountability.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of any board is a function of what the board does and how directors work together, not what it looks like. The structure and composition of the board is, in relative terms, less important. Directors take their eyes off this distinction at their peril.

An alternative approach, for more effective contributions

That the ultimate responsibility for company performance lies with the board places it at the epicentre of strategic decision-making and accountability. Consequently, if the board is to have any effect on business performance at all, it needs to maintain an active and sustained involvement in strategic management in some form.

Some commentators (and many directors and managers) have argued against the board becoming actively involved in strategic management tasks. High levels of involvement are frequently perceived by managers as interference, and close involvement can lead to a loss of objectivity in oversight. Yet boards have duties to fulfil.

Clearly, if boards are to contribute well, they need to navigate a fine line between detachment, involvement, and meddling. For that, trust, cooperation, teamwork, cohesion, and consensus building – amongst the directors and with the chief executive – are vital.

Recently published research [1] provides new insights as to how directors might work together more effectively, enabling the board to steer and guide appropriately. If the work of the board (i.e., corporate governance) is conceptualised as a multi-faceted social interaction activated by competent, functional boards, then different (improved) outcomes are possible.

The interaction itself is straightforward: an integrative assembly of necessary director capabilities (what they bring); board activities (what the board does); and, relationships and behavioural characteristics of directors (how directors act and interact) – the Strategic Governance Framework.

Necessary director capabilities include deep sector knowledge; technical expertise; business acumen; and, maturity and wisdom. The activities of the board are those described in the Learning Board Framework, a proven model, these being the setting of corporate purpose and strategy; policy making; monitoring and supervising management, and verifying performance against strategic goals and in compliance with statutes and regulations; and the provision of an account to shareholders and legitimate stakeholders.

There are five critical behavioural characteristics, as follows:

Strategic competence: Directors need to utilise their cognitive skills to exercise sound judgement on specific issues – both individually and as a group. Big picture, long-term and impartial inquisitive thinking, and a strategic mindset are particularly important if the board is to be strategically capable.

Active engagement: This enables directors to gain insights to make informed decisions, monitor the implementation of prior decisions and verify the performance trajectory of the company effectively. Indicators include adequate preparation before board meetings; close and supportive interaction between directors during meetings (read: teamwork); and an established framework within which to make strategic decisions (an approved long-term strategy).

Sense of purpose: This describes the motivation and resolve of directors to contribute to the work of the board (formulation of strategy, making of strategic and other decisions; monitoring and verification of actual performance; application of controls; and, provision of accountability) with the agreed long-term purpose of the company as a guiding principle.

Collective efficacy: The ability of directors to make informed decisions together is an antecedent of effectiveness and performance. A board’s performance is product of not only shared knowledge and skills, but also of cooperation and cooperation; empathetic interactions between directors; vigorous debate; and the situational awareness and emotional intelligence of each director as alternate points of view are aired, explored and debated.

Constructive control: Decisions made by the board in response to various inputs should be consistent with the agreed strategy and long-term goals. The mindset should be that of a coach, providing guidance rather than behaving punitively, the likes of which are more commonly associated with boards seeking to minimise perceived agency problems.

The Strategic Governance Framework outlines how functional boards can ‘perform’ corporate governance. The significance of this approach is that it marks a return to seminal understandings of shareholder board–management interaction (the board as a proxy) and corporate governance (the functioning of the board, the means by which companies are directed and controlled) that have been lost amongst the cacophony of more recent diversions and embellishments.

The behavioural dimension provides a platform for directors to interact well and for the board to make forward looking, informed decisions in a timely manner.

Unsurprisingly, the core elements are not dissimilar to the antecedents of effective teamwork (compelling direction, enabling structure and supportive context) and proven models of mission achievement (purpose, strategy, values and behaviour standards) described elsewhere.

Thus, effective corporate governance is a product of meaningful teamwork, synergistic interactions and a commitment to action amongst capable, functional directors pursing an agreed strategy and with the long-term best interests of the company in mind.

Implications for boards

Conceptually, governance is both straightforward and stable (the root word is kybernetes, meaning to steer, to guide, to pilot). However, its practice (i.e., what boards do and how directors behave) is inherently complex and quite dynamic – even more so when the incessant march of innovation, effects of disruptive forces and the miscreant motivations of some directors are considered.

The Strategic Governance Framework provides an alternative pathway for boards to exert influence by outlining requisite capabilities and tasks, and the interactions and behavioural characteristics conducive to effective contributions.

But it also challenges orthodoxy, by setting prevailing structure and composition recommendations to one side, as well as any notional physical or task separation between the board and management.

The close working proximity of the board and management that is a feature of the Strategic Governance Framework is not without its challenges. Complex group dynamics and the inherent difficulty of separating shareholder, board and manager roles (more so in smaller shareholder-managed companies or boards with so-called executive directors) can have a negative impact on decision-making objectivity in particular.

Similarly, the temptation to embrace operational detail, inadvertently confuse the roles of the board (corporate governance) and managers (business operations including strategy implementation), and shorten the strategic horizon remain very real challenges for directors around the world – as has become patently clear during the current pandemic.

If boards are to fulfil their governance responsibilities well, a clear sense of purpose supported by a coherent strategy and a well-defined division of labour is essential – regardless of the company’s size, sector or span of operations.

Early agreement on terminology, culture, the purpose of the company and the board’s role in achieving the agreed purpose provides boards a much-needed foundation upon which to assess options, make strategic decisions and, ultimately, pursue high levels of performance. Increasing numbers of boards are starting to realise that material benefits are available if they take these steps.

More generally, directors need to ensure they thoroughly understand both the business they are charged with governing, and the wider operational and strategic context within which the company operates, so their contributions are both contextually relevant and effective. A programme of continuous learning and discovery is recommended.

In addition to reading and understanding board papers, directors of high performing boards say they read widely about emerging ideas, trends and technologies, to ensure a sufficiency of knowledge about both the practice of governance and the market the company they govern operates in and new opportunities.

“In the end, boards need to remain tightly focussed on their core responsibility, which is to govern in accordance with both prescribed duties and the long-term purpose of the company in mind”.

Necessarily, effective steerage and guidance requires the board to be discerning and committed to the task at hand, using reliable governance practices in pursuit of better outcomes, lest they be diverted by spurious (and often discordant) recommendations that appeal to symptoms or populist ideals. The Strategic Governance Framework introduced here provides a useful option for boards to consider, as they strive to realise the full potential of the companies they govern.

[1] Doctoral research conducted by the author, a long-term study of boards in action.“Towards More Effective Corporate Governance” by Peter Crow, PhD, The CEO Institute is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Sign up to The Digital Governance Newsletter and the AfricanFinancials Investor Relations Insights LinkedIn page to receive practical, actionable insights to elevate your online investor relations and communications governance.

Turnkey, communications solutions for every listed company in Africa

Speak to us about IR solutions for your company

Speak to us about IR solutions for your company

AfricanFinancials works with Boards, CEOs and companies who want to build sustainable businesses through better corporate and investor communications. Our focus is online investor relations to promote secure two-way communications with investors and stakeholders.