Everywhere you look you see the ESG and sustainability narrative end with the presentation of the content on the website or PDF. But there’s a critical element missing…communicating the message of commitment to stakeholders.

This is a significant omission in the current day.

Now more than ever companies need to display and communicate long term, sustainable value to stakeholders. Revisiting corporate strategy is imperative to:

- Reinvigorate corporate purpose in light of stakeholder capitalism

- Agree what corporate values are

- Fully understand internal and external contexts

- Decide strategic priorities (where resources go)

- Determine strategic measures (to assess progress)

- Define imperative actions (exactly what to do)

All of the above is a standard narrative for companies wishing to take their sustainability commitment to the next level.

Below, Dr. Peter Crow discusses the inadequacies of adopting ESG (environmental, social and governance) principles and reporting as a complete measure of performance:

- Only two of the three elements (environmental and social) actually measure company performance

- Governance metrics like diversity, board size, remuneration, etc. are static, not outcome-driven, and add little to the board’s responsibility for long term value creation

- ‘ESG’ has almost eliminated the mention of economic performance, but profits are necessary for long term survival of an organisation and form part of their social responsibility

His solution: Monitor and report on SEE (social capital, economic and environmental) factors for a more holistic picture of the state of the business compared to ESG.

Rob

SEEing Beyond ESG

Boards have become highly topical and targets of both curiosity and criticism in the business media and, increasingly, the wider public.

During the course of the last decade or two, the conduct of boards of directors has become newsworthy. Questionable practices, a string of missteps emanating from the boardroom, company failures of various kinds and sanguine CEOs – and assertive executive teams that ‘take over’ – have seen boards become highly topical and targets of both curiosity and criticism in the business media and, increasingly, the wider public.

Regulators and institutions have responded by producing a plethora of statutes, codes, guidelines and ‘best practice’ recommendations; the intention being to establish statutory and ethical boundaries, and to steer boards towards effective practice.

Yet companies and their boards continue to suffer significant missteps or fail outright – seemingly, with metronomic regularity.

Yet companies and their boards continue to suffer significant missteps or fail outright – seemingly, with metronomic regularity – despite these interventions and (supposedly) increasing levels of awareness of what constitutes good practice. Thomas Cook, the world’s oldest travel company, is perhaps the highest profile failure in 2019. But it was by no means the only one.

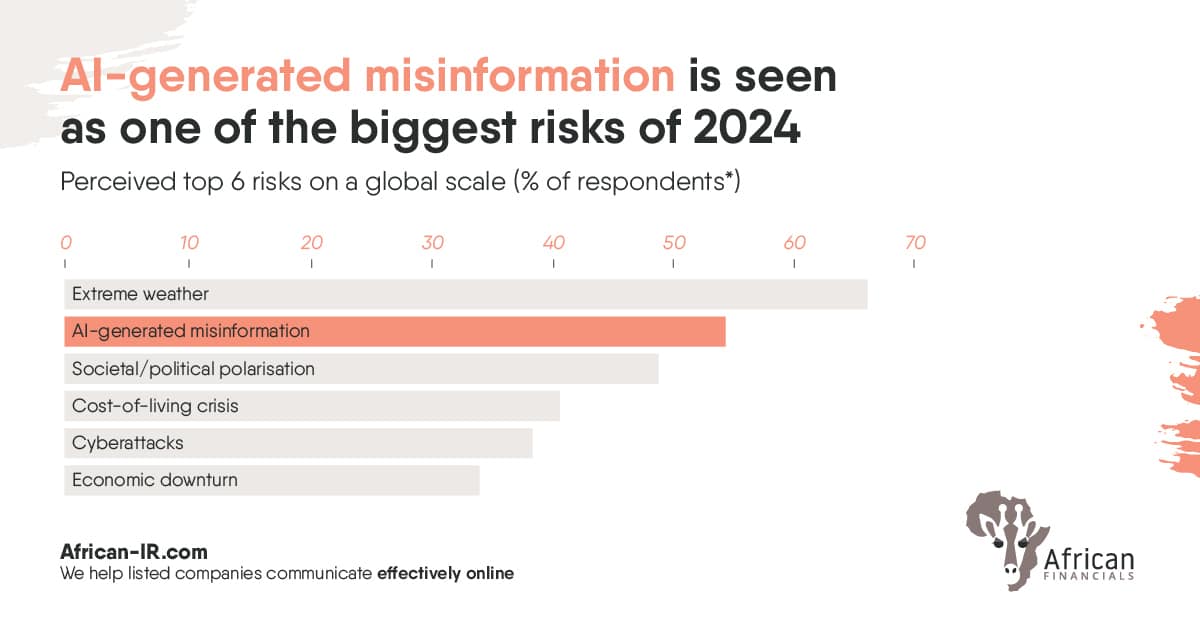

Many correspondents have encouraged boards and directors to become adept in specific risk areas. Directors, collectively, do need to be able to identify major risks to the business on an ongoing basis and, having understood them, make informed decisions to both mitigate them and maximise the chance of achieving the agreed strategy and goals.

But that is not to say directors need to become experts on climatic change, cybersecurity, disruptive technologies and other emerging risks (and opportunities) in a dynamic landscape.

Not only is this wasteful and, probably futile, but it would also result in the board taking its collective eye off its core role, which is to ensure the sustained performance of the company.

The unending procession of company failures raises many questions, such as the role and performance of the board

The unending procession of company failures raises many questions, such as the role and performance of the board, the board’s supervision of management (or lack thereof), the behaviours and motivations of directors, malfeasance and ineptitude in the boardroom, information flows and decision-making practices, and the efficacy of ‘best practice’ recommendations, not to mention the role and influence of external parties, including advisors, directors’ institutions and auditors, among others.

The plain fact is that many boards struggle to assure company continuance, much less high levels of performance. What is more, corporate governance, a term originally conceived to describe the effective work of the board of directors as it seeks to both oversee and assure business performance, is now more closely associated with a range of compliance and box-ticking activities (though this is generally denied by directors when they are interviewed).

“The social, economic, environmental (SEE) impact measure reinstates the economic dimension to its rightful place.” – ‘Dr. Peter Crow‘

Chattering class

At this point, it would be easy to concede and join the chattering class; to stand on the margins and berate all and sundry. That seemingly strong and enduring companies continue to fail on a reasonably regular basis is a cause for much concern; the societal and economic consequences are not insignificant. But let’s not get drawn into such negativity.

If companies – their boards and executive teams, in particular – are to become trustworthy again, the power games, hubris and ineptitude that pervades many boardrooms needs to be exorcised. Spurious (and often discordant) recommendations of corporate governance and how ‘performance’ should be measured (many of which appeal to observable symptoms, populist ideals or ideological biases), need to be set aside.

Mainstream recommendations need to be rethought and new approaches need to emerge.

Boards need to rethink their work and start measuring what matters, and directors themselves need to be more discerning and take responsibility for performance.

The lingering challenge, for directors both individually and collectively, is to cross this Rubicon.

Calls for boards to lift their game – even forfeit control to a much wider group of external stakeholders and self-appointed supernumeraries – are now commonplace, thanks to the actions of activist investors, proxy advisers and (increasingly) emergent lobby groups such as the Mouvement des Gilets Jaunes and Extinction Rebellion.

By way of example, Larry Fink, founder, chief executive and chairman of BlackRock, an institutional investor, writes to the CEOs of companies that BlackRock has invested in every year. In 2019, Fink encouraged company leaders to ensure their company’s purpose – its fundamental reason for being – is embodied in the business model and corporate strategy. And with it, a broader understanding of performance and how it should be measured and reported.

Fink encouraged company leaders to ensure their company’s purpose – its fundamental reason for being – is embodied in the business model and corporate strategy.

ESG: an adequate measure of company performance?

Essentially, boards need to embrace their responsibility for both ensuring the on-going performance of the company they are charged with governing and providing a straightforward account to shareholders and legitimate stakeholders.

The underlying ethos needs to be one of service: the board and executive working harmoniously together, as a team in service of the company and the purpose for which it exists. And therein lies a clue to effective corporate governance, board oversight and reporting.

That the problem is multifaceted and dynamic, not structural, suggests the optimal reporting solution is likely to be multifaceted as well.

The idea of using a range of financial and non-financial measures to assess company performance was normal practice until the early 1970s. But things began to change relatively quickly from the late 1960s, primarily as a consequence of the rise of neo-liberalism. The tipping point was an article by Milton Friedman, who espoused the one and only social responsibility of business was to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase profits.

Almost overnight, a broad church of managers, boards, shareholders and activists embraced Friedman’s thesis (with evangelical zeal in many cases) to justify an exclusive focus on profit maximisation. And with it, interest in other (non-financial) indicators of corporate performance waned. For the next three decades or so, the dominant measurement framework was economic.

However, things began to change around the turn of the century, with the emergence of proposals such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) to encourage companies to become more socially accountable.

A bevy of academics, consultants and politicians implored boards and executives to think more broadly about the company’s contribution (and impact) on society. The objective of much of this rhetoric seems to have been to establish a counterbalance to perceived excesses of capitalism in the years following Friedman’s article appearing in the New Yorker and changing expectations.

ESG (environmental, social, governance) in particular has gained an enthusiastic following as a more complete measure of performance.

Its emergence has coincided with the rising tide of concerns about the effects of the doctrine of shareholder maximisation promoted by Friedman.

Even the Business Round Table, an influential lobby, has taken a stand, issuing a statement in August 2019, which signalled it stepping back from shareholder primacy. Signed by 180 chief executives of America’s largest enterprises, the statement is, in effect, a reversal of the BRT’s previous policy position.

Many others have argued that the widespread adoption of ESG principles (as a measure of CSR) could redress some of the imbalances and inequities that have become apparent as company leaders have pursued profit as the exclusive measure of performance and success.

“ESG has, without doubt, increased the time and energy spent by companies demonstrating their ‘performance’ as a good corporate citizen.”

But what is acceptable ‘performance’ exactly, and how should it be measured? Is ESG adequate as the gold standard of performance measurement?

Author Peter Drucker’s insightful maxim (what gets measured gets managed) is relevant for sure, but two things limit the usefulness of ESG as a sufficient measure of corporate performance.

First, only two of the three elements actually measure company performance (E and S illuminate a company’s commitment to various environmental and social goals, respectively). The third, G, measures something else: a collection of proxies to indicate the (supposed) performance of the governance function, that is, the board of directors. These include diversity, board size, remuneration and audit committee mandate. The problem is that these are observable and static inputs, not consequential outputs or outcomes arising from company operations.

Second, and perhaps more significantly, the ESG construct relegates economic performance to such an extent that it is not mentioned. But economic performance is necessary if an enterprise is to endure over time.

“Profits are in no way inconsistent with purpose – in fact, profits and purpose are inextricably linked.

Few are as clear as Fink on this point:

“Profits are in no way inconsistent with purpose – in fact, profits and purpose are inextricably linked. Profits are essential if a company is to effectively serve all of its stakeholders over time – not only shareholders, but also employees, customers, and communities.

“Similarly, when a company truly understands and expresses its purpose, it functions with the focus and strategic discipline that drive long-term profitability. Purpose unifies management, employees, and communities. It drives ethical behaviour and creates an essential check on actions that go against the best interests of stakeholders.”

Further, agreement (in relation to the efficacy of ESG as a suitable measure of company performance) is far from universal. Many directors have lamented – some at length, but almost all privately – that the promulgation of ESG is counter-productive.

Boards have in practice become more concerned about adherence to prescribed ‘best practice’ ESG frameworks.

Rather than focussing boards on performance dimensions beyond financial measures (the intention), boards have in practice become more concerned about adherence to prescribed ‘best practice’ ESG frameworks.

The ‘G’ (governance) element in particular adds little in terms of focussing boards on the creation of value over the longer-term. That is because the measurement of board performance (that is, the board’s effectiveness) carries an inherent assumption – that governance practice is directly linked to company performance in a causal sense. It is not.

A more complete picture of company performance is needed

If boards and shareholders are to understand company performance well, the three capitals that fuel sustained business performance (SEE – namely, social capital, economic and environmental) need to be monitored and reported in a holistic manner.

The restoration of the economic dimension of performance to its rightful place alongside the social and environmental dimensions offers a more complete assessment of the company’s actual performance in the context of the wider market within which it operates. This proposal moves beyond ESG and its inherent limitations.

Boards considering this proposal will find it is not onerous. Appropriate measures of social, economic and environmental performance that are both congruent and consistent with the company’s purpose and strategy need to be identified, and a high-level dashboard developed to provide a holistic summary of company performance.

Such an approach is arguably more straightforward and cost-effective than the compliance-oriented reporting (comply or explain) outlined in various corporate governance codes, or the six capitals proposal that has been heavily promoted by the Integrated Reporting Council in recent years. It has the added benefit of being useful in small-, medium- and large-scale firms.

And what of governance?

Rightly understood, governance is about providing steerage and guidance (a lesson dating from the Greeks), the means by which companies are directed and controlled (hat tip to Sir Adrian Cadbury).

As such, governance is a function performed – not a capital consumed nor a consequential outcome or result of company operations – and, therefore, Drucker’s maxim should be applied.

A section entitled ‘board performance’ within the annual report should suffice.

So, to the courageous question: has the time arrived to SEE beyond ESG as a more insightful measure of corporate performance and the consequential value created?

If the objective is to achieve a more balanced assessment of the company’s performance in the context of corporate purpose, strategy and the wider environment within which it operates, SEE is worthy of close consideration.

Peter Crow PhD

Dr. Peter Crow is an accredited company director and chair, and an advisor and educator with deep expertise in corporate governance, strategy and effective board practice. He also speaks and writes on topical board matters and undertakes governance research. A dynamic thinker, his insightful guidance has proved invaluable to the fortunes of a wide range of enterprises, across five continents.

Peter has a doctorate in corporate governance and strategy (a pioneering study explaining how boards influence firm performance).

This article was first published in Winter 20 edition of Ethical Boardroom.

Sign up to The Digital Governance Newsletter and the Sustainability and Investor Relations Insights LinkedIn page to receive practical, actionable insights to elevate your online communications governance and ESG stakeholder relations.

Turnkey, communications solutions for every listed company in Africa

Speak to us about IR solutions for your company

Speak to us about IR solutions for your company

AfricanFinancials works with Boards, CEOs and companies who want to build sustainable businesses through better corporate and investor communications. Our focus is online investor relations to promote secure two-way communications with investors and stakeholders.